"Sumac Leaves" is the fifth edition of new woodcuts for late winter 2014. It is also the sixth in a series of leaf prints. Previous releases are "Bur Oak Leaves," "Aspen Leaves," "Gamble Oak Leaves,"" Bigtooth Maple Leaves," and "Redbud Leaves." All of these may be viewed in the Woodcuts Gallery.

New Woodcut: "Redbud Leaves"

The fourth woodcut release for late winter 2014 is titled "Redbud Leaves." The cordate (heart-shaped) leaves make a simple statement.

New Woodcut: "Scarab"

"Scarab" is the third edition of woodcuts for late winter 2014. These beetles, celebrated by ancient royalty and contemporary ecologists alike, are distributed worldwide in tropical and temperate regions. They are a common grassland insect, and some members of the group are best known as dung-burying beetles.

New Woodcut: "Black-Necked Stilts"

The second woodcut edition of the late winter season depicts a trio of Black-necked Stilts. These striking wading birds with their dramatic black and white plumage and long red legs nest in northern Utah, northern Nevada, southern Idaho, southeastern Oregon and other areas in the West. They are adapted to (have been selected by) shallow waters (marshes, lake margins, mudflats, etc.).

New Woodcuts: "Polar Bear"

The next five blog posts will introduce five new woodcuts for late winter 2014.

The first, "Polar Bear," was released at the Holiday Open House Exhibit in Salt Lake City. Besides being an appropriate subject for a black ink woodcut, the bear is also the tragically popular 'poster animal' for climate change. The minimal title "Polar Bear" was selected from a longer list-- Great White Bear, Ice Bear, Snow Bear, Rain Bear, the Last Polar Bear, On Thin Ice, Endangered, Extinct, etc. (I have a lot of time to think of titles while I am carving the maple block and printing the prints.) The owners of the prints may choose their own titles. Click on the image to go to the Woodcut Gallery for buying information.

Holiday Art Party: Exhibit and Sale, December 5th, 2013

Environmental Commentary: "Fighting Nature"

This 1992 FoxSense graphic has often been criticized as being a bit of an overstatement.

For me, the overstatement originates from the enthusiastic marketing, sales, and use of toxic chemicals for a wide variety of reasons and uses, including spraying poisons on our crops (our food) and watersheds (drinking water).

And then, of course there's a global amphibian decline, colony collapse disorder (bees), and biological magnification of toxic chemical concentrations in food chains everywhere (including the Arctic).

For an expanded discussion, please read "The Safe, Non-toxic Garden" essay in the spring 2013 issue of EdibleWastatch.

If you have a choice, which overstatement would you like to base your health on?

"Fighting Nature" from Foxsense. © 1992 Fred Montague

Environmental Commentary: Diet Matters

The table shown below is a part of the handout I use for my "Global Imperative for the Local Garden" presentation.

As you examine the information, pay particular attention to the amount of grain (and therefore land) that the typical American diet requires per person per year. It is about four times that of a mainly plant-centered diet typical of many developing countries.

For the time being, the Mediterranean diet seems to be a wiser choice, from a health, longevity, and sustainability perspective.

An exclusive plant-centered diet, for most of humanity, is an economic necessity. It would also be the model if we were trying to see how many humans we could support (probably temporarily) on Earth.

The Mediterranean diet is diversified, healthier, and more easily satisfied by what can be grown by an individual or family in a backyard garden.

Diet Choice Impacts. A handout from Fred's "The Global Imperative for the Local Garden" presentation.

From the Gallery: "Mayfly" print

The pen-and-ink drawing entitled "Mayfly" depicts a Midwestern fern and a Midwestern mayfly. The shape of the leaves of the fern (Genus Asplenium) struck me as remarkably similar to the profile of the mayfly's wings. I found both, posed as shown, in a central Indian prairie-edge stream valley.

The print edition of 200 sold out several years ago.

"Mayfly" photolithograph, © Fred Montague.

Gardening: Harvest Rainwater

This page from my Gardening: An Ecological Approach outlines a simple method for collecting rainwater from your rooftop. In most of the western U. S., gardens require more water than can provided by our modest rainfall. Collecting rainwater, where legal, can give you a little insurance during the especially dry times.

"Harvesting Rainwater." From Gardening: An Ecological Approach. © Fred Montague

Environmental Commentary: "Heading for the Cliff"

Here's another page from my sketchbook of graphical visualizations of environmental issues-- climate change again.

The top figure (I) shows humans shifting our living conditions to another state, a warmer environment. The sphere rolling uphill represents the human enterprise heading for conditions for which it is not immediately adapted-- abnormal conditions. And for an operation tailored to normal conditions, abnormal conditions are problematic. This scenario assumes that we immediately stop emitting from any source carbon dioxide that exceeds the Earth's capacity to sequester it. In other words, our net additions of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere are ZERO. This is not likely, despite the fact that we are the most "highly educated" and "technologically advanced" gang of humans ever to have existed.

The lower figure (II), under current conditions of concern and commitment, is a more likely possibility. There is only so far we can push the current array of multicellular organisms (mostly plants, fungi, and animals) into an environment for which they are not adapted. By the way, humans are multicellular organisms.

Of course there are probably more possibilities. Can you think of any?

"Climate warming possibilities" from the sketchbook. © Fred Montague

From the Gallery: "Autumn Treat"

The photolithograph (print) "Autumn Treat" features a Yellow-rumped Warbler (Dendroica coronata) feeding on poison ivy fruit in October. I made the original drawing in north-central Indiana. The migrating warblers gathered our poison ivy fruit one day and planted it the next in south-central Indiana.

The eastern (and northern) subspecies is called the "Myrtle Warbler." The western subspecies is called "Audubon's Warbler."

The field guides are full of examples of speciation in action. Speciation is Nature's process of creating new species. Populations of a species become geographically isolated, and if they remain separated for enough generations, they will eventually be genetically isolated. Once that occurs, they are separate species. Other examples include the Northern Flicker (Yellow-shafted Flicker in eastern North America and Red-Shafted Flicker in the western states) and, among common mammals, the mule deer (the Rocky Mountain Mule Deer in the Rockies and the Black-tailed Deer in the Pacific Northwest).

Whenever you encounter an animal species that includes recognized "subspecies" (or a plant species with recognized "varieties"), then you know that biological diversity, in these particular cases, is potentially increasing.

This limited edition of prints (200) is nearly sold out. Each print measures 8"x 10" . The price in $40.

"Autumn Treat", photolithograph of a myrtle warbler. © Fred Montague

Gardening: Reasons to Garden #5

The fifth "reason to garden" is an appeal (originally to students in my wildlife and environmental science classes) to save wild places and wild organisms.

Wilderness preservation and wildlife conservation are daunting tasks, and the challenge seems overwhelming. But, the simple act of tending a small garden, has the potential to begin to address the challenge.

To Save Wilderness

The Earth's human population currently exceeds 7 billion people, and it is increasing by more than 200,000 people per day! To feed the expanding human family, modern industrial agriculture is causing serious environmental impacts. Ironically, agriculture may not be sustainable as it is currently practiced. Furthermore, to propose that we must plow every square food of remaining wild land to feed the additional three billion people on Earth by 2050 is a plan of desperate human arrogance. Such a plan is the ultimate condemnation of everything that is wild and free on this oasis planet. W may be able to save wilderness by grow an increasing share of our food in places where people already live-- cities, towns, settlements, neighborhoods. Here,gardens offer the graceful possibility of living with, rather than to the exclusion of, the other five million species of organisms with which we share the planet.

Illustration from Gardening: An Ecological Approach. © Fred Montague

Environmental Science Classroom: More "Range of Tolerance"

The May 13, 2013 post presented a typical "range of tolerance" diagram that attempts to explain the way that different species thrive along specific portions of an environmental gradient.

In Nature (real life), of course, there are many environmental gradients (or factors). In Gardening: An Ecological Approach, I have added the logical extension to the explanation by adding more environmental factors. Now a landscape of "species nodes" begins to appear. One is depicted in the lower portion of the illustration from the book.

The impression for me is that there are many unique combinations of intersecting environmental gradients, each with a species thriving under those conditions.

Range of tolerance. © 2013 Fred Montague

Gardening: Reasons to Garden 4

In Gardening: An Ecological Approach I list several important reasons to grow a garden. My post on April 12, 2013 briefly explained reason #1 (to grow food for health) and my post on May 1, 2013 outlined reason #2 (to enhance soil fertility). The post on May 10, 2013 gave reason #3 (to produce next year's seeds).

Here is reason #4...

To Provide for Other Organisms

Many other organisms live in the ecological garden besides edible plants. These include microbes, earthworms, soil algae, spiders, fungi, insects, toads, and birds-- to name only a few. To encourage beneficial insects, for instance, the gardener may plant a continuously blooming array of flowers to provide refuge and alternative food sources for pollinators and predators. A variety of insects in balanced populations is desirable. A weed patch is useful, productive, and beautiful in its own way. In the garden, diversity promotes health and stability.

Illustration from Gardening: An Ecological Approach. © Fred Montague

Wildlife Field Notes: Rodents

The graphic below is from a series of Wildlife Field Notes that I published through the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service.

Rodents are at the larger end of the spectrum of the 'little things that make the world work'-- in biologist E. O. Wilson's words. They, along with microbes, protists, arthropods (especially insects), little fish, and small mammals provide critical ecological functions upon which larger animals depend.

The rodents serve as important "energy transformers" that convert hard-to-digest plant foots into rations for a wide array of meat-eaters. Foxes, weasels, coyotes, hawks, and owls are just some of the carnivores that include rodents (especially mice and voles) in their diets.

Their generally small size makes them very prolific, for mammals. Their population densities are often very high. Some vole (meadow mice) populations in good habitat, and in peak years, may number 100 individuals per acre (or 64,000 per square mile hypothetically). Their small size is counteracted by their large numbers and important roles in ecological communities.

"Rodents". © Fred Montague

Environmental Commentary: Sun Energy

There are two fundamental phenomena that have enabled life to emerge and thrive on planet Earth. One is the continual flow of solar energy from the sun, and the other is the cycling of a finite amount of material on earth.

The book page reproduced below is from my handmade book One Earth.

Sunlight is a perpetual energy source-- at least in time frames meaningful to humans. I am always amazed that today's environmentalists and energy experts persist in calling solar energy a "renewable" energy source. It is not renewable; it is inexhaustible. Maybe solar energy would gain more traction as our wisest choice if more people realized we will never run out of it.

"Sun Energy" from One Earth. © Fred Montague

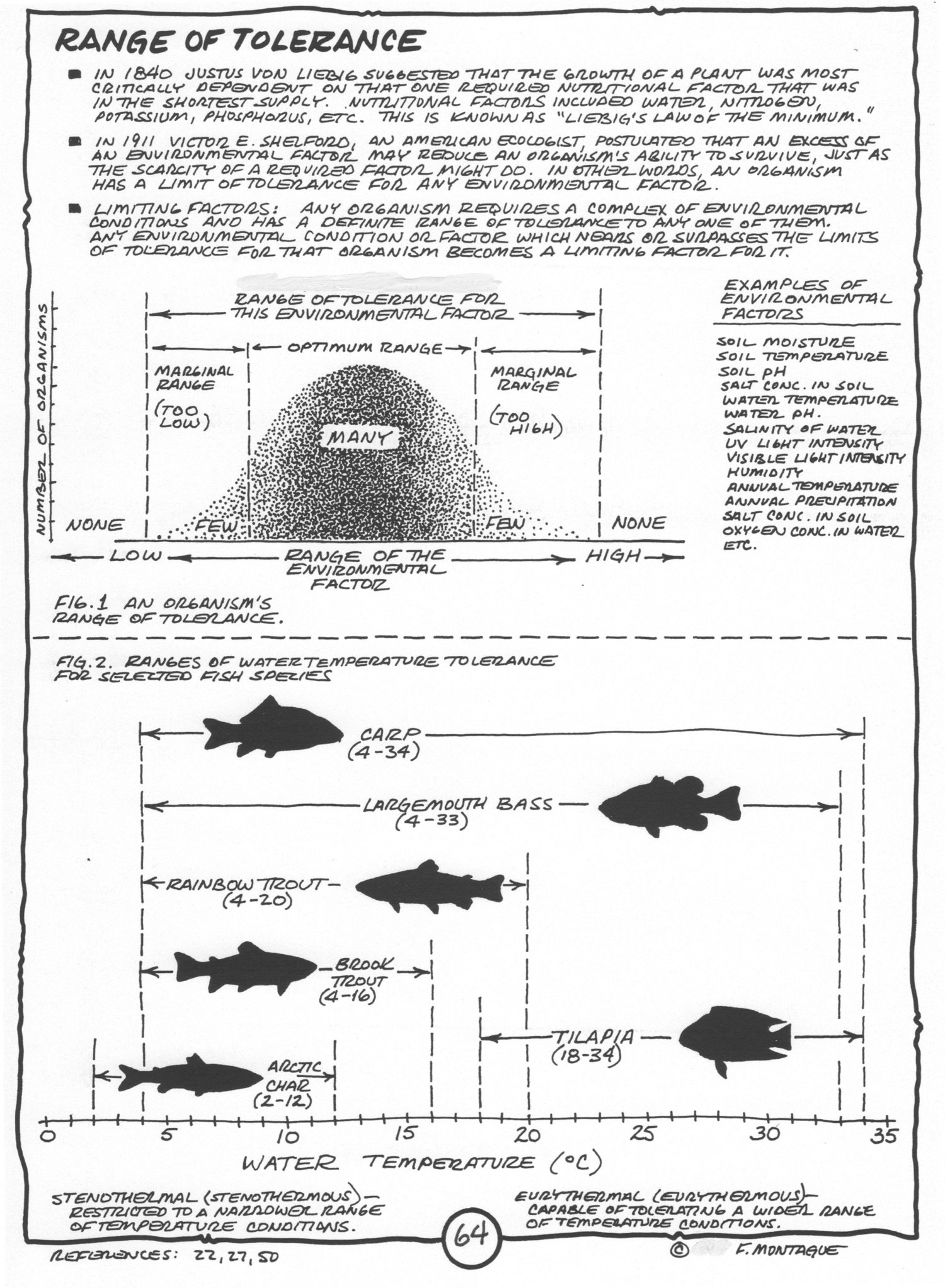

Wildlife Science Classroom: Range of Tolerance

In all of my teaching, one of the most important ecological concepts I believe that I shared with students is the concept that a population of organisms lives within a fairly specific range of environmental conditions.

The illustration below is a page from my wildlife textbook Wa-Maka-Skan. It is a simplified depiction that shows the general theoretical concept for one environmental factor. The bottom portion shows that for various fish species, one of the important environmental factors affecting their distribution and survival is water temperature.

This concept is relevant today, especially as human-caused global change alters the living conditions of species. Environments are shifted out from under the adaptations of the species. The faster the change and the larger the animal, the more problematic the situation becomes.

Range of Tolerance from Wa-Maka-Skan. © Fred Montague

Gardening: Reasons to Garden 3

In Gardening: An Ecological Approach I list several important reasons to grow a garden. My post on April 12, 2013 briefly explained reason #1) (to grow food for health) and my post on May 1, 2013 outlined reason #2 (to enhance soil fertility).

Here is reason #3...

To produce next year's seeds

One of the more conservative activities associated with ecological gardening is raising "heirloom" plants. In addition to producing food, these plants also yield seeds that more faithfully replicate the parent plants. In other words, they breed "true." This is in contrast to growing hybrid plants from most commercially-grown seeds. Unfortunately, seeds saved from hybrid plants tend to produce offspring that are unpredictable regressions to ancestral forms. The gardener who saves seeds from her best heirloom plants is conserving (and even increasing) biological diversity while becoming more self-reliant.

Illustration from Gardening: An Ecological Approach. © Fred Montague

From the Sketchbook: Another Way to Visualize Global Change

Here are more brainstorming exercises to help visualize stability and change.

Images 1 and 2 depict two stability states, one robust and one tenuous.

Image 3 seems (to me) to be a reasonable representation of our current circumstances.

Images 4 and 5 are a bit more ominous (especially image 4) because they suggest abrupt changes. For large organisms and complex cultures adapted to relatively stable conditions, abrupt change is troublesome.

Ways to visualize stability and change. © Fred Montague